This year has marked an extraordinary chapter of learning and growth at Technology for Wildlife Foundation. Through the years, we've been honoured to collaborate with passionate individuals and organisations fiercely committed to environmental and wildlife conservation. Our deepest gratitude goes out to everyone who has walked this path with us at TfW. As we prepare to close our doors, we take a moment to reflect on the milestones of this year, in our final annual summary.

Exploring mangroves during an early morning excursion with Tanmayi Gidh from Rainmatter Foundation.

We began the year with a field excursion to a mangrove patch in Goa, accompanied by Tanmayi Gidh of Rainmatter Foundation. During this visit, we looked at the ecosystem, talked about its significance as well as had an in depth discussion of our work. Tanmayi's article, published in the first quarter of the year, captures our conversation and can be found here.

Poster for announcing the exhibit on the social media, read more here.

Our exhibit, (Understanding) Mangrove Carbon, was selected as part of Science Gallery Bangalore’s Carbon exhibition last year, and it opened to the public mid-January. This exhibit highlights our work on remote sensing methods to estimate carbon sequestration by mangrove ecosystems, combining research conducted over by TfW over the years using drone and satellite data. We collaborated with visual artists who brought our scientific findings to life through multimedia interpretations. We are deeply grateful to our collaborators - Himanshi Parmar, Svabhu Kolhi and Gayatri Kodikal, for their continued support throughout the year of preparation. The digital material from the exhibit is also available on our website.

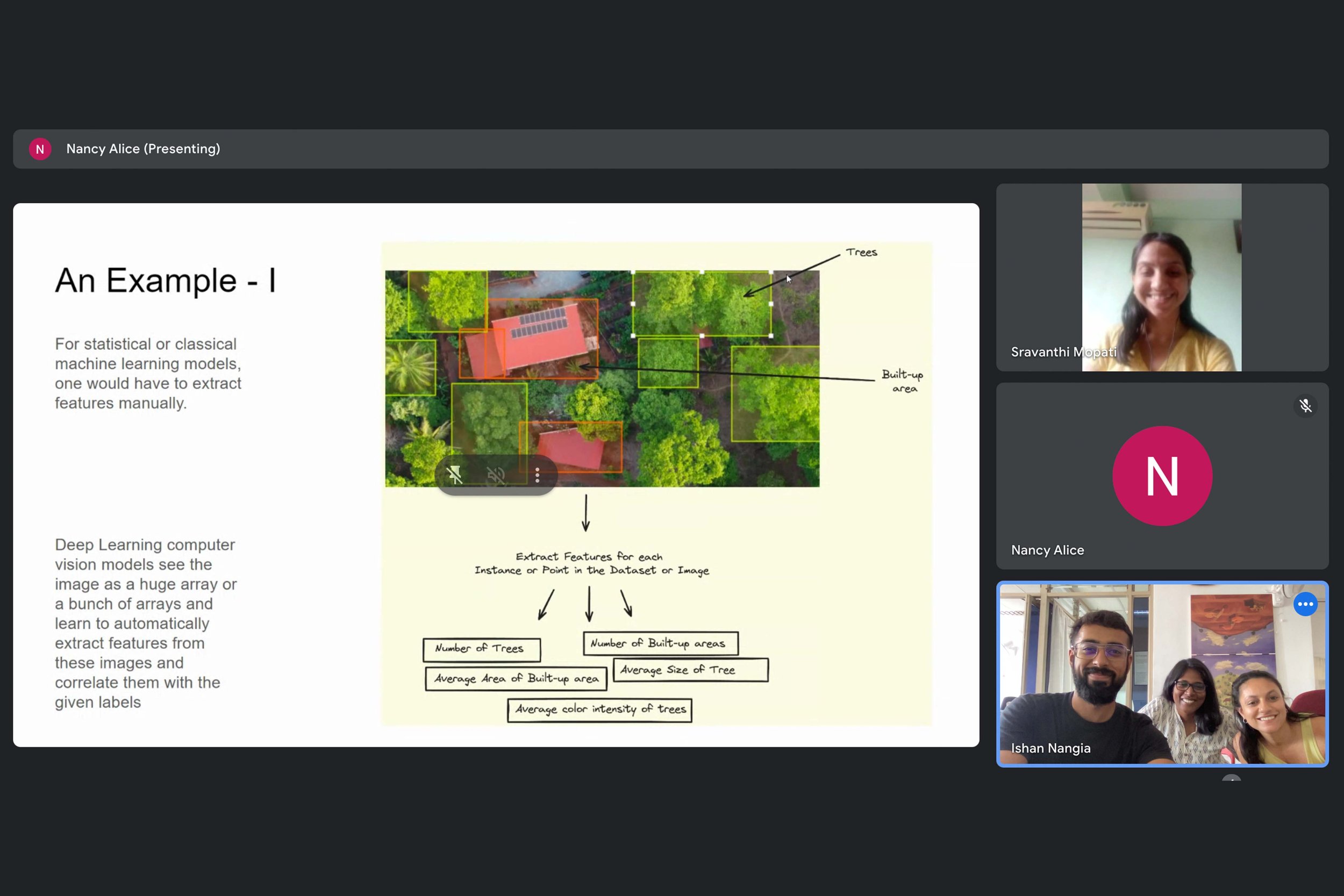

Screengrab from Part-I of an internal workshop on series on the different aspects of working with images.

In February, we held an internal workshop series on the different aspects of working with images within our organisation, including drone, satellite and hand-held camera imagery. Since we use all three types, the workshops provided an opportunity to discuss how each of us approaches and analyses these images, and to establish a shared vocabulary for smoother collaboration. Part-I of the series, led by our Data Analyst, Ishan Nangia, covered the use of computer vision, particularly in drone imagery.

Group picture from the day-long working meeting with team members and collaborators on the Restoration in the Western Ghats project, February 2024.

Later in the week, we held a day-long working meeting with team members and collaborators to explore how technology can support ecological restoration in the Western Ghats. Our field partners, Alex Carpenter, Cristina Toledo, and Aishwarya Krishnan, joined us, along with Dr. Madhura Niphadkar and Dr. Kartik Teegalapalli, who served as experts in labelling degradation factors in our drone imagery. Arjun Singh from ERA India also participated in the discussion. Learn more about this project here.

Nandini Mehrotra in the field with students from ATREE in Bagepalli, Karnataka.

In mid-February, we compiled our comprehensive workflow for using drones in conservation mapping and data collection. This was immediately implemented in a workshop initiated by Dr. Rajkamal Goswami for students of ATREE at their field station in Bagepalli, Karnataka. Conducted by TfW team members: Sravanthi Mopati, Nandini Mehrotra, and Nancy Alice, the workshop provided a technical overview of integrating UAVs and their data into the toolkit for landscape restoration. The sessions covered drone fundamentals, applications in conservation, flight planning, and post-processing of data. Participants also engaged in hands-on training with various software tools and participated in a field demonstration.

The TfW team with the '(Understanding) Mangrove Carbon' exhibit in the background.

After the workshop, our team returned to Bangalore, where we had the opportunity to view the (Understanding) Mangrove Carbon exhibit in person at Science Gallery Bangalore.

Project teams from WCT and TfW in action, Bihar.

Towards the end of the month, we travelled to Bihar with the Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) to study behaviour of Ganges river dolphins. This also marked our third season of collaborating with WCT to study these river dolphins. Using small quadcopters, we captured videos of dolphins in pre-identified hotspots, gathering valuable information that was previously difficult to obtain. The data is now being analysed to estimate the size, body condition, and age brackets of dolphins in this region, with plans to publish the findings in a paper later this year.

Group picture from our field trip to Mhadei, March 2023.

In March, following up on our day-long workshop in early February, we visited our site partners Alex Carpenter and Cristina Toledo, in Mhadei with conservationists Benhail Antao and Arjun Singh joining us on this field trip. Since 2022, TfW has been collaborating with the Goa Botanical Sanctuary to explore the use of technology for ecological restoration on their 150 hectares in the Goan Western Ghats. Our work focuses on developing open-source methods that integrate ground, UAV, and satellite data to assess land degradation and guide restoration efforts. We hope that the methods we are developing, which will soon be published, will benefit others working on similar projects in the Western Ghats.

Screengrab from Part-II of an internal workshop on series on the different aspects of working with images.

As our field season slowed, we were able to focus on other projects, including our report on using drones for conservation in India. Towards the end of the month, we conducted Part-II of our internal session on image analysis, led by Nancy Alice. This session explored the different ways team members interpret images, reflecting on our earlier team discussion about varying perspectives on image analysis.

The TfW core-team and its Directors in Goa, April 2024.

In April, the TfW core-team and its Directors gathered for a heartfelt discussion about the difficult decision to close the organisation. These conversations marked the beginning of a careful process to complete our existing projects and slowly wind down operations.

Team members conducting drone calibration experiments in to get accurate error margins.

While off-the-shelf drones are useful, we still need to adapt them for specific tasks. During our analysis of field data from Bihar, we discovered that certain values, like height and camera angles, required calibration. Led by Ishan Nangia, our team worked in April and May to refine error margins in the drone's measurements, experimenting with simple materials and available spaces. These findings are now featured in a blog post on calculating real-world object sizes from drone images. For a detailed breakdown of the process and results, read Ishan’s blog post here.

We also conducted online workshops with Earthfocus on methodologies for the use of drones to plan and monitor a restoration project, during these two months.

Playtesting the Elephant Board-game amongst friends in Goa.

Over the past few years, we have been developing a board game focused on elephant corridors and human-wildlife interaction. We have play-tested and subsequently refined the game in various settings, including work environments, home, and structured forums. In May, we conducted a playtest with a control group in Goa, which included wildlife biologist Dr. Nandini Velho. The feedback from this session has also been documented for incorporation.

Aerial view of olive ridley turtles recorded during the joint field survey in March 2023.

Later in May we also published a case study of our work on tracking near-shore olive ridley turtles using UAVs in collaboration with WeRobotics, a global network of practitioners using drones for public good.

Over the years, we’ve explored and learned how to use appropriate softwares to create an efficient workflow with off-the-shelf quadcopter drones for conservation and scientific research. In June, our team focused on documenting this process in simple ‘how-to-?’ blogs so other conservationists can benefit from it and continue to do impactful work with it. This section on our website can be accessed here.

Illustrated by Svabhu Kohli, the artwork depicts TfW’s technology-driven conservation efforts across various ecosystems.

At the end of the month, we publicly announced the closure of the organisation, alongside the release of Svabhu Kohli's illustration showcasing TfW’s technology-driven conservation efforts across various ecosystems.

Screengrab of Ishan's last team-call with TfW.

We also bid farewell to Ishan Nangia, who is moving on to his new role, while working on his independent initiative, ReefBuilder. At TfW, he used computer vision and mathematics to extract conservation-relevant data from drone footage.

Additionally, Nandini Mehrotra appeared on the Heart of Conservation podcast with Lalitha Krishnan, discussing the legacy of ethical and collaborative processes with technology at TfW for impactful grassroots action.

We published our fourth Grove update in early July, covering the period from mid-April to December 2023.

TfW team picture from the final retreat in July 2024.

In mid-July, the TfW team held our final retreat in Mollem, which included a night walk in the forest and we were able to observe bioluminescent fungi. This retreat provided an opportunity for the team to reflect on our conservation journey and share closing thoughts.

We also hosted a heartfelt farewell for our team members and collaborators to share stories and experiences from our time together at TfW. It was a warm occasion where we reflected on our achievements, discussed the impact of our work, and conducted interviews to capture our journey. The evening was marked by gratitude and nostalgia: a celebration of meaningful connections and dedication that defined our efforts at TfW.

Over the past few years, we’ve been dedicated to creating a report that documents the use of UAVs for conservation in India. We owe a special thanks to Shivali Pai, whose MPhil research at Liverpool John Moores University laid the foundation for this important work. Toward the end of 2022, Shivangini Tandon joined us, conducting additional interviews in a semi-structured format, adding valuable insights to the project.

Wings for Wildlife team-members (L-R) Nandini Mehrotra, Nancy Alice and Shivangini Tandon.

In July, we were proud to publish ‘Wings for Wildlife’ highlighting how drone technology is being applied to wildlife and environmental conservation in India. Through 15 case studies, the report showcases drones' potential in biodiversity conservation, animal behaviour studies, and habitat mapping, while also addressing their limitations. The report is available for free download on our website. We also began printing the final copies of the book and celebrated this milestone in-person with team members Nandini Mehrotra, Nancy Alice and Shivangini Tandon (above L-R).

With this, our ongoing projects concluded, and we began documenting and archiving our work. Throughout July and August, the TfW website saw major updates, including new information and blogs. The website will continue to serve as an archival resource after the organisation's closure.

In-person workshop with consultants reflecting on our conservation efforts in Goa, July 2024.

As part of this effort, we held an in-person workshop with consultants from Imago as well as with Sanket Bhale of WWF-India to document our work. Additionally, we began impact assessment meetings to reflect on our collective learnings. These meetings are helping us evaluate our initiatives, celebrate successes, address challenges, and ensure that our experiences make a meaningful contribution to the wider conservation field. The study is ongoing, and we look forward to sharing it publicly soon.

TfW team (L-R): Sravanthi Mopati, Nandini Mehrotra, Ishan Nangia, and Nancy Alice, July 2024. Picture courtesy of Svabhu Kohli and Farai Divan Patel.

As we wrap up our operations, we are proud of the legacy we've created together and the lasting impact of our efforts. The resources, reports, and insights we've developed will remain accessible on our website, continuing to support and inspire conservationists and enthusiasts alike.