(Cross-posted from the Hindu Business Line, October 19th 2015)

Unmanned aerial vehicles are flying robots that provide some of the benefits of manned flight without its attendant risks and inconveniences. Commonly known as drones, they proved their worth on the battlefield during the 1973 Yom Kippur and 1982 Lebanon wars, after which numerous military forces began implementation of their surveillance and weaponised drone programmes. Today, India is reported to have some 200 Israeli-made drones in service, and is in the process of developing indigenous ones for military use. Civilians, however, are banned from flying drones.

Drones are not just used for military purposes; they have also been used by civilians around the world for a diverse set of non-conflict use cases. These include assisting aid agencies during humanitarian crises, helping farmers with their fields, providing a new perspective to journalists, letting conservationists rapidly monitor wildlife and conduct anti-poaching patrols, as well as simple recreational activity; flying a drone can be a lot of fun.

Drones, thus, have commercial value; they provide a much cheaper alternative to manned flight, and enable applications that were impossible earlier. Unfortunately, most new technologies come with their own dangers, and drones are no exception. They can occasionally crash. This matters most when the drone being flown is large and heavy, as a crash can damage property and harm people. Drones also occupy airspace that is used by manned aircraft, and an in-air collision or even a near-miss, could be disastrous. These are dangers that could occur unintentionally. However, there is also the fear that drones could be used to intentionally cause harm.

For these reasons, the relevant regulatory bodies of some countries have limited the public use of drones until these concerns can be addressed. In India, the Directorate General for Civil Aviation (DGCA) completely banned their use by civilians as of October 7, 2014. However, the authorities in other countries haven’t gone as far; in the US, the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) allows the civilian use of drones with caveats, while their commercial use is licensed. While the various countries of the European Union (EU) currently have multiple regulations covering drone flights, the European Aviation Safety Agency intends to create common drone regulations, with the intention of permitting commercial operations across the EU starting in 2016.

The regulatory authorities of these countries have understood that drones are here to stay, and that their use can be extremely beneficial to the economy. A report by the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), a non-profit trade organisation that works on “advancing the unmanned systems community and promoting unmanned systems”, states that by 2025, the commercial drone industry will have created over 100,000 jobs in the US alone, with an economic impact of $82 billion. Drones can also contribute to the export market. For example, in Japan, where commercial drones have been licensed since the 1980s, Yamaha Corp has been producing drones for aerial spraying for agricultural purposes which are now exported to the US, South Korea, and Australia, generating $41 million in revenue for Yamaha in 2013-14. That’s small change compared to the current global market leader’s expected sales for 2015. SZ DJI Technology Co Ltd of Shenzen, China, was only founded in 2006, but by 2015, they controlled 70 per cent of the global commercial drone market and a higher percentage of the consumer drone market, for an estimated revenue of $1 billion.

These countries and companies have addressed the inherent dangers of drone technology by looking at technology- and policy-based solutions. The FAA and the UK’s Civil Aviation Agency (CAA) prohibit the flying of drones within five km of an airport or other notified locations, and drone manufacturers like DJI and Yamaha could enforce these rules by incorporating them into the drone’s control software. This means that a drone will be inoperable within these restricted zones. Outside these zones, drone misuse can be treated as a criminal offence. In the US, two individuals were recently arrested for two separate drone-related incidents: in one, the operator’s drone crashed into a row of seats at a stadium during a tennis match and in the other, the operator flew his drone near a police helicopter.

In India, the DGCA’s October 2014 public notification states that due to safety and security issues, and because the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) hasn’t issued its standards and recommended practices (SARPs) for drones yet, civilian drone use is banned until further notice. One year later, there are still no regulations available from the DGCA; the ICAO expects to issue its initial SARPs by 2018, with the overall process taking up to 2025 or beyond. Meanwhile, the loss to India’s economy, and the threat to its national security, will be enormous. Today, it is still possible to import, buy, build or fly small drones in India, despite the DGCA’s ban. This means that drone-users in India currently exist in an illicit and unregulated economy, which is far more of a threat to the nation than regulated drone use could ever become.

Finally, flying drones safely in India will require research and development to understand how they can be best used in India’s unique landscape. Such R&D occurs best in a market-oriented environment, which will not happen unless civilian drone use is permitted. Building profitable companies around drone use can be complicated when the core business model is illegal.

Like civil aviation regulators in other countries, the DGCA should take a pro-active role in permitting civilian use of drones, whether for commercial use or otherwise. Creating a one-window licensing scheme at the DGCA, where drone users only have to apply for permission from the ministries of defence and home affairs in special circumstances, would be a useful first step. Setting up a drone go/no-go spatial database would allow the DGCA to discriminate between these use cases and could also be mandatorily encoded into drone systems by their manufacturers. The DGCA should also discriminate between drones based on their size and weight; the smaller and lighter the drone, the less risk it poses. This should be recognised while regulating drones.

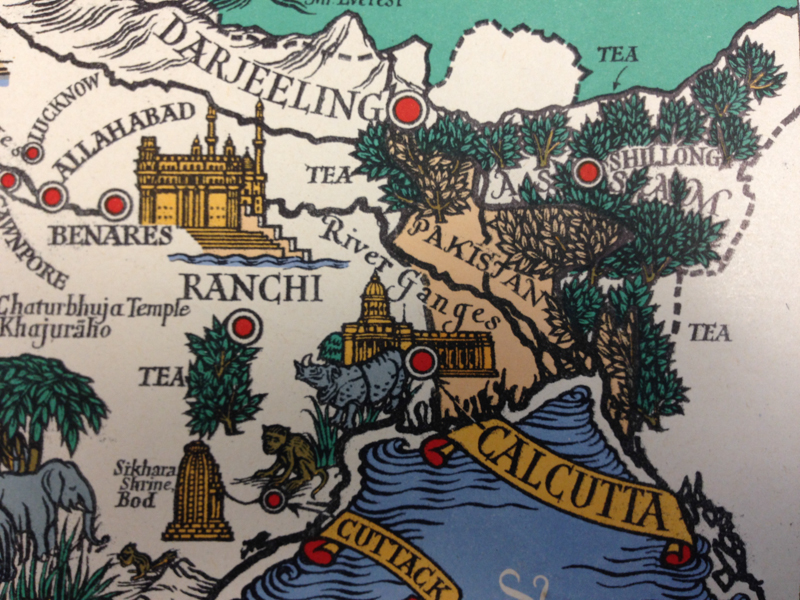

Whether it is to assist fishermen with finding shoals off the Indian coastline or conducting rapid anti-poaching patrols in protected areas across the country, mapping refugee settlements in Assam and Bengal for better aid provision or assessing the quality of national highways, drones can transform the way we conduct operations in India. Thus, a blanket ban on civilian drones in India is more of a hindrance to development than a solution to a problem. Drones are here to stay and the sooner India’s civilians are allowed to use them, the faster we can put them to work.

[ This article was commissioned by the Centre for the Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania and is also available on their blog. ]