This blogpost was originally posted on the WeRobotics blog (link) on the 8th of October 2020

The global civilian drone industry is currently in a growth phase. From its initial beginnings in the mid-2000s as a hobbyist activity to its warranting regulatory supervision to its current status as a potential game-changer for national economies, the drone industry seems to have weathered it all. Even with the pandemic and associated lockdowns, the drone industry still has the potential to grow, providing as it does the option of ensuring that work gets done safely and hygienically. Over these years, the number of both drone users and the various applications of drone-acquired data have grown massively.

“It’s possible for a project to comply with existing regulations and legislation, and even be commissioned by the state, and still be deficient from an ethical perspective.”

As with most emerging technologies, drones have influenced and exacerbated a plethora of complex social interactions. When drones are used without adequate consideration of their impact, they can inflict serious harm on individuals and communities. In India, policies, regulations, and social norms around drone use have not kept pace with the technological applications, especially around what constitutes safe and ethical drone use. At Technology for Wildlife, we are conservation geographers and drone pilots; thus, we are also participants in the Indian drone industry. We’ve come to realise that accepting certain work proposals would put us in ethically complicated and questionable situations that could potentially compromise our desire to do good. However, each time we choose to decline a project that does not fit with our values, we know there are enough other drone operators out there for the project to go ahead anyway. It’s possible for a project to comply with existing regulations and legislation, and even be commissioned by the state, and still be deficient from an ethical perspective. There is a clear need to create and implement guidelines for the drone industry regarding the ethical operation of drones to complement the government-mandated regulations.

In this context, in late 2019, we applied for the WeRobotics Unusual Solutions Competition, intending to understand what would be required to have participants in the nascent drone industry commit to conducting ethical operations. Today, we’re pleased to present our work in a report titled: Towards Incorporating Ethical Considerations into Indian Civilian Drone Operations.

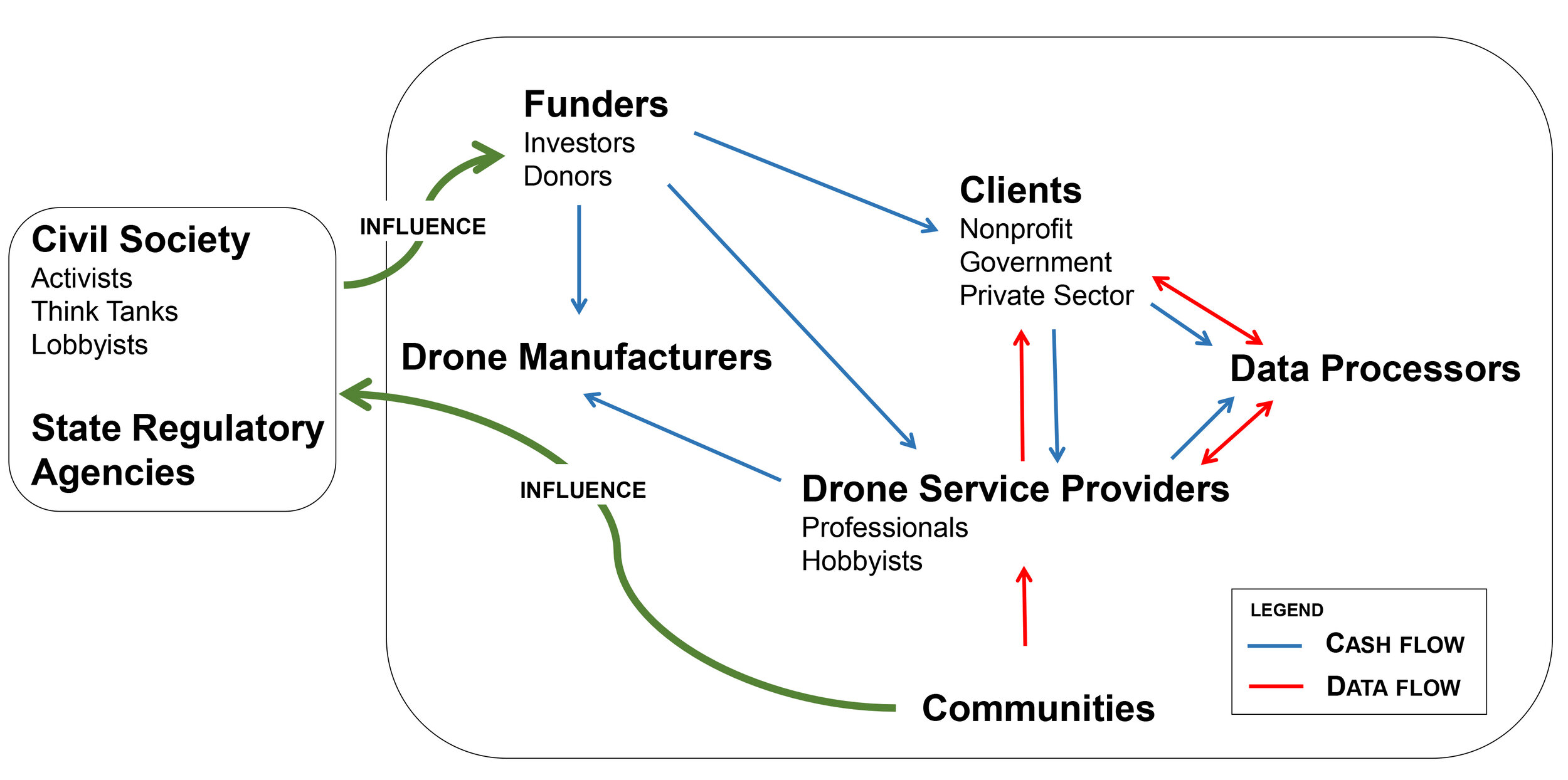

Rather than providing prescriptive rules on ethical operations, we’ve used our research and sectoral knowledge to put together a roadmap to what we believe ethical drone operations should look like in the Indian context, and how and why specific stakeholders should be engaged. This report is intended (to quote from it directly) for “anyone in, or engaging with, the drone industry and will be particularly relevant to those who intend to build solutions that would address the social implications of civilian drone use.” While we have focused on the Indian drone industry, it is quite likely that our work is also applicable to other countries with similar contexts.

We hope that in these troubled times, this report is one of the many pieces required to ensure that drone operations are empathetic, considerate, and ethical, both in India as well as globally.